The intricate story of “cacao” and “cocoa” to describe Theobroma cacao fermented cocoa beans and subsequent chocolate confections is deeply rooted in cultural exchanges, linguistic evolutions, and global commerce. The subtle difference between these two terms carries a weight of history, bringing to light their individual and shared journeys from ancient civilizations in central and south america to today’s bustling global markets.

At present, we encounter authors and influencers trying to coin distinctive meanings to each one of the phonemes, and it is true, as we will explain, that both terms now have some subjective differentiation, but before rushing to establish definitions, let us review the etymology of the word.

Origins of “Cacao”: The Precious Seed of the Americas

The word “cacao” traces its origin to the Nahuatl word “cacahuatl,” used by indigenous peoples in present-day Mexico to refer to the seeds of the Theobroma cacao tree. European exposure to “cacao” began with their first encounters and exchanges with these indigenous cultures.

Hernán Cortés (early 16th century)

In the early 16th century, Hernán Cortés discovered the Aztec’s prized “xocolatl,” a bitter, frothy drink made from fermented cacao beans, during his exploration of the New World.

This beverage, integral to Aztec rituals and esteemed by the nobility, was seasoned with a vanilla extract and chili, presenting a novel taste to Europeans. Cortés reported his findings, including the method of xocolatl’s preparation and its cultural significance, to King Charles I of Spain, using “cacao” to describe the bean and drink, without reference to “cocoa.”

This encounter introduced cacao to Europe, initially greeted with curiosity. Over time, adaptations like adding sugar made chocolate a favored luxury among the aristocracy, with “cacao” laying the foundation for chocolate’s linguistic and cultural assimilation into Europe. This marked the onset of Europe’s enduring fascination with chocolate, transitioning from an exotic Aztec beverage to a European culinary delight without an early distinction between “cacao” and “cocoa” for the tropical plant.

Cortés’s accounts played a pivotal role in chocolate’s historical journey to becoming a cherished part of European diet and luxury.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1526)

In his influential “Historia General y Natural de las Indias” (1526), Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés provided one of the first detailed European accounts of the cacao tree and its seeds, offering a rich description of cacao seeds based on direct observation in the New World.

Oviedo meticulously noted the cultivation, appearance, and indigenous uses of Theobroma cacao, strictly adhering to the term “cacao” without reference to “cocoa,” preserving the original terminology he encountered.

Bernardino de Sahagún (late 16th century)

In the late 16th century, Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar and ethnographer, compiled the “Florentine Codex,” an unparalleled ethnographic work that offers an exhaustive insight into Aztec society, including their agricultural practices, dietary habits, and economic systems.

Within this comprehensive study, Sahagún devoted significant attention to the cultivation and usage of cacao among the Aztecs, providing one of the earliest and most detailed accounts of its role in their culture. His writings meticulously describe how the Aztecs revered cacao not just as a food item but as a potent symbol of wealth and social status, often used in religious rituals and as a form of currency. Sahagún, adhering closely to the terminology of his indigenous informants, consistently used the term “cacao” to describe the plant and its products, reflecting the term’s original Nahuatl roots without any reference to “cocoa.”

By using the term “cacao” throughout his documentation, Sahagún’s work preserves the linguistic and cultural authenticity of the Aztec relationship with cacao. His detailed observations provide invaluable insights into pre-Columbian practices and underscore the importance of cacao within Aztec culture, long before the European adaptation of the product and the eventual linguistic shift that introduced “cocoa” into the English language.

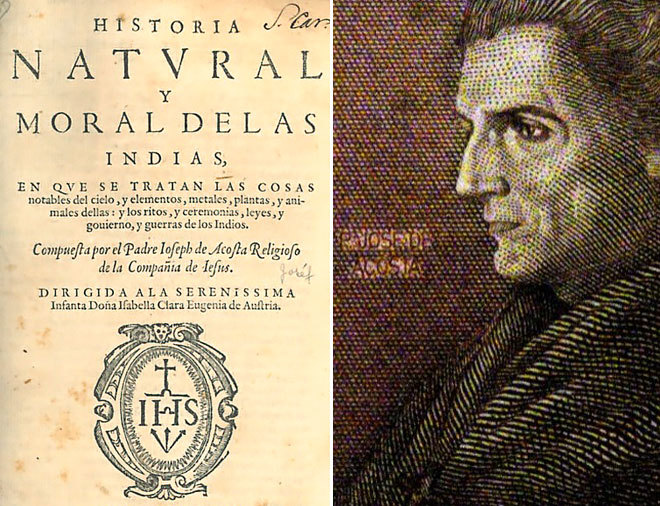

José de Acosta (1590):

In 1590, José de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit missionary and naturalist, published “Historia Naturalis,” a comprehensive work detailing his observations of the natural world and indigenous cultures of the New World.

Within this seminal text, Acosta provides one of the earliest European insights into the role and significance of cacao among indigenous societies. His narrative places a strong emphasis on “cacao,” adhering closely to the terminology used by the native populations he encountered. Acosta’s use of the term “cacao” is deliberate, reflecting his commitment to accurately documenting the customs and practices related to this important crop.

Acosta’s work is particularly notable for its exploration of cacao’s economic and social importance in indigenous communities, highlighting how cacao beans were not only consumed as a beverage but also used as a form of currency. He meticulously described the preparation methods and the cultural rituals surrounding cacao consumption, offering a window into the complex relationship between the people of the New World and this vital crop.

There is no mention of the term “cocoa” in Acosta’s accounts, indicating that the distinction between “cacao” as the raw product and “cocoa” as the processed form had not yet emerged in the European lexicon at the time of his writing.

Peter Martyr d’Anghiera (early 16th century):

In the early 16th century, Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, an Italian historian at the Spanish court, authored “De Orbe Novo,” a collection of letters and reports detailing the discoveries and cultures of the New World. This work stands as one of the earliest European accounts providing insights into the indigenous use and cultivation of cacao. Martyr, through his meticulous compilations, emphasized “cacao” in line with the indigenous terminology, carefully documenting its significance in the societies encountered by Spanish explorers. His references to “cacao” are pivotal, showcasing his effort to preserve the original terms used by the native peoples, thereby providing a direct and unaltered glimpse into their customs and economic practices surrounding this crucial crop.

The absence of the term “cocoa” in his writings indicates that the focus was purely on the natural and unprocessed state of cacao as it was known and utilized by the native cultures. Through his detailed accounts, Martyr d’Anghiera contributed significantly to the understanding of cacao in the European context, marking an early step in the long history of cacao’s journey from the New World to becoming a global phenomenon.

Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma (1631)

In 1631, Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma, a Spanish physician and writer, contributed significantly to the literature on New World discoveries with his treatise “Chocolata Inda.”

This work is dedicated entirely to the exploration and advocacy of chocolate, delving into its preparation, benefits, and cultural significance. Notably, Colmenero de Ledesma’s discourse centers on the term “cacao,” reflecting the ingredient’s authentic and unprocessed form as it was known among the indigenous populations of the Americas.

His deliberate use of “cacao” throughout the treatise signifies an effort to maintain the integrity and originality of the chocolate tradition as inherited from the New World. There is no reference to “cocoa,” which suggests that the focus was squarely on celebrating cacao in its most natural and revered state, as a testament to its roots in ancient cultural practices.

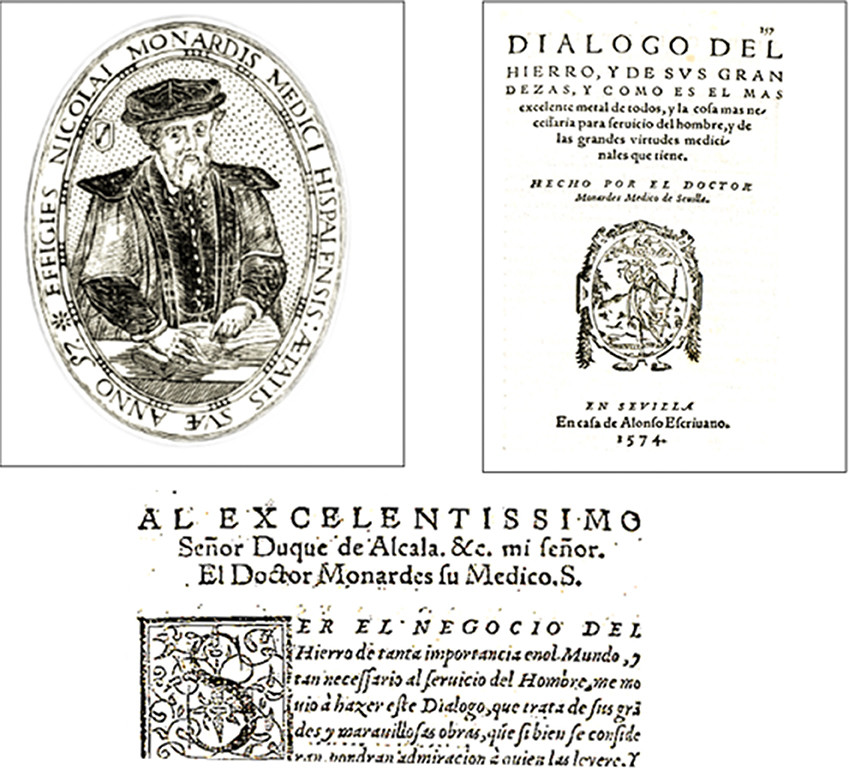

Nicolás Monardes (1574)

In 1574, Nicolás Monardes, a Spanish physician and botanist, published “Natural History of the West Indies,” a comprehensive work that brought the flora and fauna of the tropical regions of the New World to the European audience’s attention.

Within this extensive catalog of American natural resources, Monardes dedicates a section to the uses and benefits of cacao, presenting it as a marvel of the New World. Notably,

Monardes uses the term “cacao” to describe this valuable commodity, aligning with the indigenous nomenclature and emphasizing its originality and authenticity. His decision to use “cacao” rather than any Anglicized version or adaptation highlights his respect for the source culture and his intent to present the information as accurately and faithfully as possible. There is no indication that Monardes referred to the product as “cocoa,” suggesting a clear preference for maintaining the traditional term that encapsulates the cultural and historical significance of the cocoa bean.

“Cocoa”: A Linguistic Evolution of Theobroma cacao

The term “cocoa” likely emerged as a result of the repeated mispronunciation of “cacao” and solidified its position in the English lexicon. This evolution is evident in some of the earliest English texts. Sir Hans Sloane’s “A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica” (1707) describes the cacao-based drink using the term “cocoa,” highlighting its prevalence in English writings by the 18th century.

While “cacao” originally denoted the plant or its raw product, “cocoa” came to symbolize its powdered form or sometimes the beverage derived from it. This distinction, however, became blurred over the centuries. The dominance of “cocoa” in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in English-speaking countries, reflects a shift towards more industrialized versions of the product.

Interchangeability and Modern Use: The Cacao-Cocoa Conundrum

An apt illustration of the interchangeability of these terms for Theobroma cacao is found in the stock exchange. The symbols for cacao futures use the term “cocoa,” even though the traded product is the raw, unprocessed bean.

In recent years, industry influencers have advocated differentiating “cacao” and “cocoa.” The former represents unprocessed, “natural,” or “raw cacao” versions usually found in health food stores, while the latter is reserved for industrialized cacao product variants, especially the Dutch-alkalinized powder. This distinction encapsulates the broader trend of consumers’ growing demand for transparency, authenticity, health benefits and purity in their food products.

Production process: from cacao beans to cocoa butter and cocoa powder

As we know, the cacao bean is obtained from harvested theobroma cacao fruit pods. Cacao beans are usually fermented by the farmer. Afterwards, the fermented beans are sent to grinding processing facilities where they are ground into cacao nibs; then milled into chocolate liquor and finally pressed into cocoa butter and cocoa powder. This production process can be carried out in an ultra-industrialized way, with the cacao subjected to extremely high temperatures, or more simply and naturally.

Cacoa emerging from “dutching” or alkalizing

The process of “dutching” or alkalizing cacao plays a pivotal role in how the product came to be predominantly known as “cocoa” in many markets. Introduced in the early 19th century by Coenraad Johannes van Houten, a Dutch chemist, this method involves treating cacao beans with alkaline substances to neutralize their natural acidity. This not only makes the cocoa powder less bitter and more soluble in water but also darkens its color, leading to a milder, flavor profile and a smoother texture in the finished chocolate product.

As this process became standard in the manufacturing of chocolate, the term “cocoa” became more closely associated with the alkalized cocoa powder product. The distinction between non-alkalized “cacao” and alkalized “cocoa” powder became more pronounced, with “cocoa” signifying the product that had undergone this specific treatment. This terminology solidified in consumer minds and industry labeling, differentiating “cocoa” as the more processed, dutched variant of the cacao product, and further entrenching the cocoa denomination in the language of chocolate products.

Conclusion

The intertwined histories of “cacao” and “cocoa” reflect centuries of cultural, economic, and linguistic dynamics. As we look to the future, it’s essential to acknowledge and appreciate the rich past of these terms and the products they represent.

As cacao consolidates as a healthy product, distinct terminology is beginning to emerge, and time will begin consolidating new definitions.

Whether enjoying a piece of raw cacao nibs or sipping hot cocoa, one is partaking in a tradition that spans millennia and continents.